Cared for by the National Trust, the Farnes are one of the UK’s most important wildlife habitats, home to thousands of seabirds and destination for hundreds of adult grey seals in late autumn and early winter.

Globally, the Atlantic grey seal is one of the rarest seal species and is a protected sea mammal. Global numbers are estimated to be around 300,000 with half living in British and Irish waters.

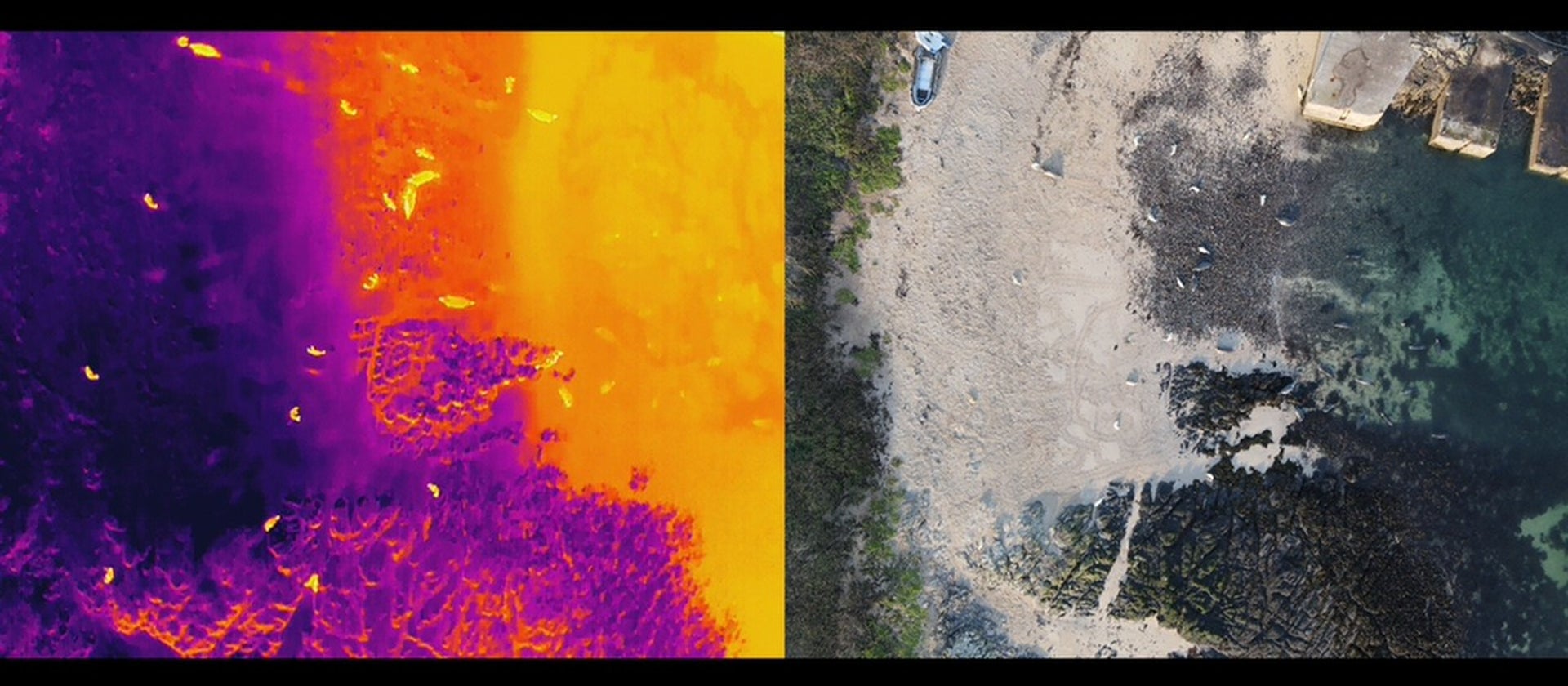

The rangers who work on the islands have traditionally counted the seals every four days using dye, and in 2018 used a drone for the first time to help verify numbers. This year, the rangers are working with researchers at Newcastle University, Oxford University, the Sea Mammal Research Unit (SMRU) and Skeye to continue trials counting the seals with a drone that uses two separate cameras, one to film the seals from above as visible with the naked eye, and the second using a thermal imaging camera.

Using drones to monitor and count wildlife is a relatively new practice. It allows conservationists to look at large areas easily and quickly, count whole populations rather than just a sample, and is far less intrusive and stressful for the animals than the close interaction of human led surveys. It also allows the team to count pups on outlying islands in difficult conditions.

Using drone photography also allows the rangers to quickly and accurately count the seal pups on the images using computer based machine learning – making the surveys quicker, more cost effective and more accurate than was previously possible.

Thousands of adult seals return to the Farne Islands each year to pup – typically giving birth to one pup. The survival rate varies from year to year but in spite of this, the last recorded seal pup numbers in 2019 reached a record high of 2,823 – an increase of 62 per cent over the last five years. The team were unable to carry out the count last year due to the covid pandemic but believe that the numbers would have continued their upward trend.

The very first pup was seen on the Wamses, one of the rockier outcrops at the start of October, and this week the first seal pups have been born on the largest island, Inner Farne.

Ranger Thomas Hendry commented: “The sighting of the first pup of the year triggers the start of the seal pup count, and we’re excited this year to see if the upward trend continues. The increase in numbers in recent years is thought to be down to the lack of predators or disturbance and the fact that the grey seals are generalist rather than specialist feeders.

“This year we are still counting the seals every four days in some locations, weather permitting. Once born, they’re sprayed with a harmless vegetable dye to indicate the week they are born. Using a rotation of three or four colours allows the rangers keep track of the numbers.

“We are using a drone again this year which as well as filming the pups is fitted with thermal imaging technology to help make the count more accurate and less stressful for the seals.

“The drone gives us an excellent view of the islands and from the clear images we can count the total numbers of seal pups born on each island. It also allows us to see onto the smaller islands more frequently which can be more challenging to visit at this time of year due to difficult sea conditions.

“Having the extra thermal imaging technology is particularly useful now that the islands are supporting more and more pups and the population is denser. It will hopefully also allow us to detect any seal pups that sadly don’t survive, so that they aren’t accidentally included in our numbers.

“As the footage is taken whilst we are carrying out a visual count, we can compare different counting methods to check against the numbers we get on the ground.

“We take great care when using the drone to ensure the seals remain undisturbed at this vital time to ensure none of the pups are abandoned.

“Since we started using the drone in 2018 it consistently seems to pick up more seals than we can see through on the ground monitoring, which has become increasingly difficult over the past five years with the colony becoming much denser due to the increasing number of pups being born. Therefore there may have been a slight undercount from ground counts when it was the only method we could use previously.”

The rangers have also observed that the seals now no longer pup on some of the very small islands. This may be because they are no longer suitable, being more susceptible to storms and sea level rise.

Tom continued: “Monitoring the growing population is vitally important so that we can manage the island habitats accordingly. The UK is incredibly important for grey seals, as we estimate we have around 44 per cent of the global population.”

The seals are born with bright white fluffy coats. Although the pups can swim at an early age they don’t normally leave the breeding colony until they have been weaned and after they have moulted their soft white coats. This happens when they are about two or three weeks old and their dense grey waterproof fur grows through. The pups stay with their mother on the islands for around three weeks before they leave the Farnes to feed, typically returning to breed once they have matured.

For more information about the Farnes visit www.nationaltrust.org.uk/farne-islands For information on how you can help support our work on the coast, visit https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/appeal/coast-campaign-appeal